Analys

Natural gas – A Glimpse into Supply, Demand, and Prices

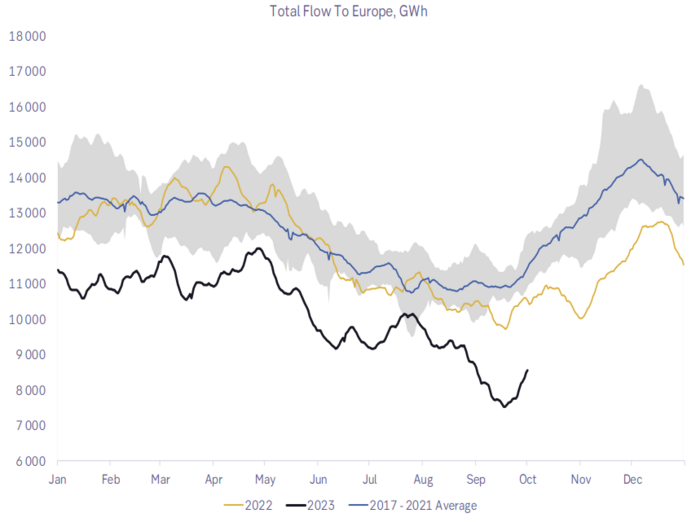

Supply: Recent weather patterns across Europe have been milder than usual, leading to a delayed onset of the heating season. The weather forecast for the next two weeks predicts a continuation of this trend. As a result, EU TTF spot prices have decreased, leading to a reduced volume of LNG imports to Europe in September and early October. Current imports stand at about 3.3 TWh/day, down from 4.0 TWh/day at this time last year, and significantly lower than the 6.0 TWh/day at the beginning of summer 2023.

Although peak maintenance on the Norwegian Continental Shelf (NCS) concluded in mid-September, it is scheduled to continue for another month. Despite this, Norwegian natural gas exports to Europe are encouraging, currently at 2.6 TWh/day, though still below the historical average of 3.4 TWh/day. Meanwhile, Russian supplies have increased marginally from 0.6 TWh/day in mid-summer to 0.85 TWh/day currently, yet they remain 2.65 TWh/day below the historical average. Overall, Europe’s current supply is roughly 8.65 TWh/day, clearly lower than the historical average of 11 TWh/day for this period.

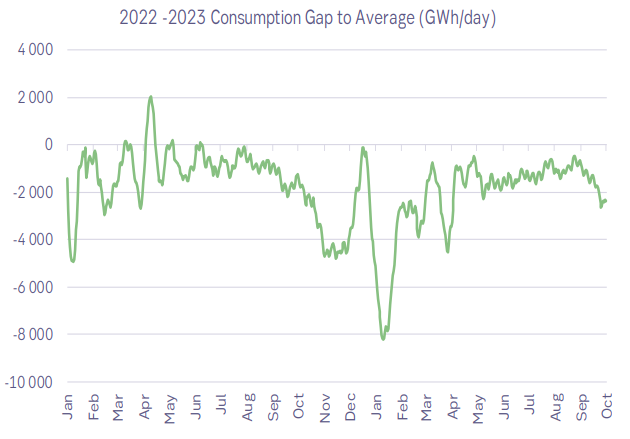

Demand: Last year witnessed a significant decrease in European natural gas demand, which has persisted longer than anticipated. Present consumption rates are slightly lower than last year at 7.5 TWh/day and are 2.5 TWh/day below the historical norm. Current consumption patterns resemble those typically seen in August—a month characterized by European holidays and peak maintenance on the continent’s natural gas infrastructure. The prevailing mild weather is likely to further reduce consumption in the coming weeks. Moreover, industrial gas consumption among the EU’s major consumers (DE, FR, IT, BE, UK, & NL) has remained consistent with October 2022 levels, at 1.9 TWh/day, which is 0.6 TWh/day below historical averages.

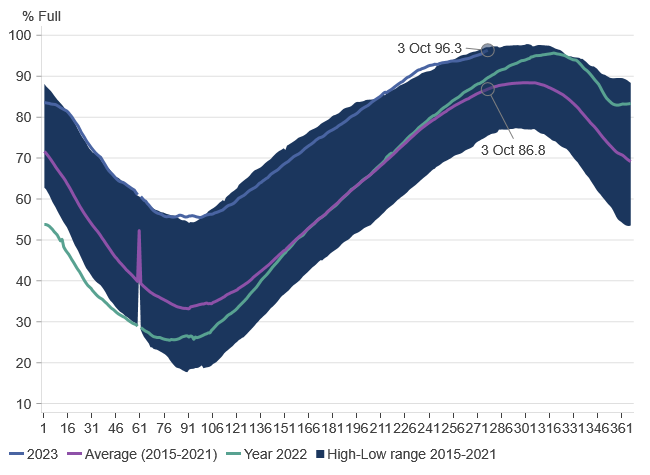

Inventories: EU natural gas storage levels are nearing capacity, with current levels at 96.3%, 9.5% higher than the five-year average. This excess has contributed to the decline in spot prices. With storage nearly full, some stored volumes must be sold at discounted rates to accommodate incoming LNG shipments. However, longer-term prices for the upcoming months and winter 2023/24 remain relatively stable. Although concerns about potential shortages for the upcoming winter are lessening, end-of-April 2023 inventory levels will influence the market for the following seasons.

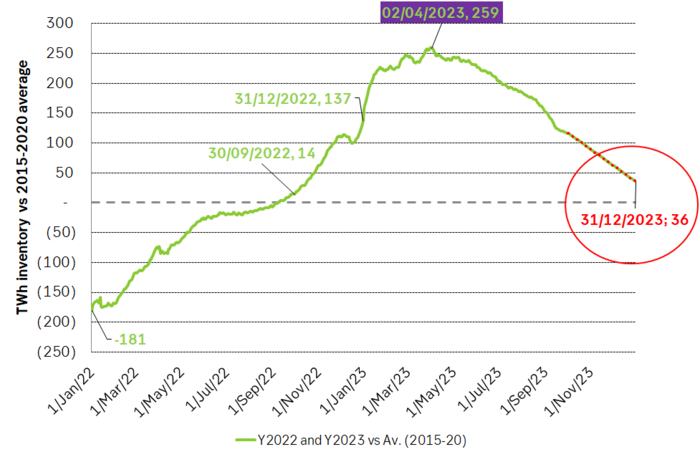

Inventory Outlook: Given the ongoing demand reduction, inventories are expected to remain robust in the short term. However, as the end of the year approaches, projections indicate a convergence towards a more ”normal” inventory level. This means that by year-end, inventories will be 36 TWh above typical levels, a significant reduction from the 259 TWh surplus in early April 2023. Presently, the surplus stands at 116.8 TWh. The trend suggests that inventory levels will approach historical norms, resulting in a tighter EU natural gas market as peak winter approaches.

Price Dynamics: Europe’s mild start to the heating season has proven beneficial, especially during a time of peak maintenance at the NCS and potential risks of decreased global LNG supplies (Australian LNG). The high current inventory levels have significantly minimized the risk of natural gas shortages for the upcoming winter. However, as the heating season progresses, the EU inventory drawdown will be significant.

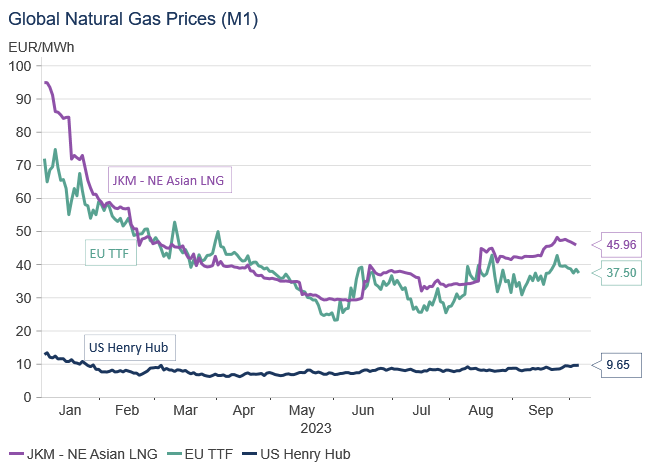

Current price dynamics reveal that the EU TTF forwards (M+1 and winter 2023/24) have declined “too far” compared to the Japanese LNG price. LNG is, and will continue to be, the marginal supplier of natural gas to Europe.

In 2022, the EU witnessed unprecedented levels of LNG imports. To realize this, the EU natural gas price consistently traded at a premium — averaging EUR 15.6/MWh over the front-month Japanese LNG price throughout the year. By the second half of 2022, this premium escalated to an average of EUR 30/MWh. However, the tables have turned: currently, the EU price is at a discount of EUR 8/MWh to the Japanese LNG price for November (M+1) and EUR 5.5/MWh for Q124.

We foresee this trend as short-lived. We believe that, as winter approaches, the EU TTF natural gas price will not only match but potentially exceed the Japanese LNG price by a premium of EUR 5-10/MWh. In our view, the current EU TTF natural gas forwards are undervalued relative to the Japanese LNG price and will likely see a correction, ensuring the EU continues its robust LNG imports. Standing by our early September Gas price projection, we anticipate the average TTF spot price for Q4 2023 to be around EUR 55/MWh and the aggregate for 2023 to settle at EUR 45.5/MWh.

Analys

Tightening fundamentals – bullish inventories from DOE

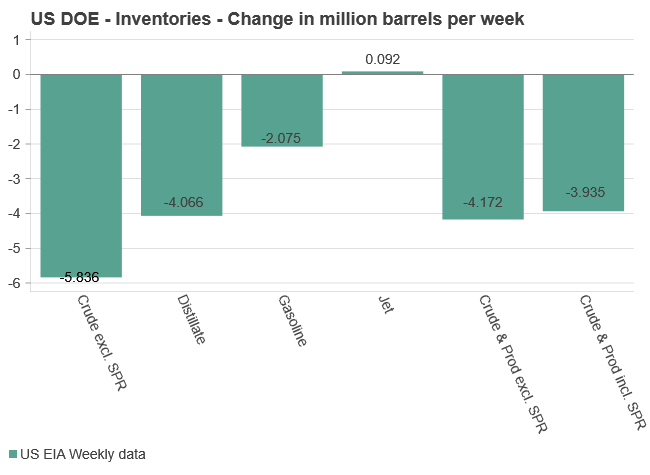

The latest weekly report from the US DOE showed a substantial drawdown across key petroleum categories, adding more upside potential to the fundamental picture.

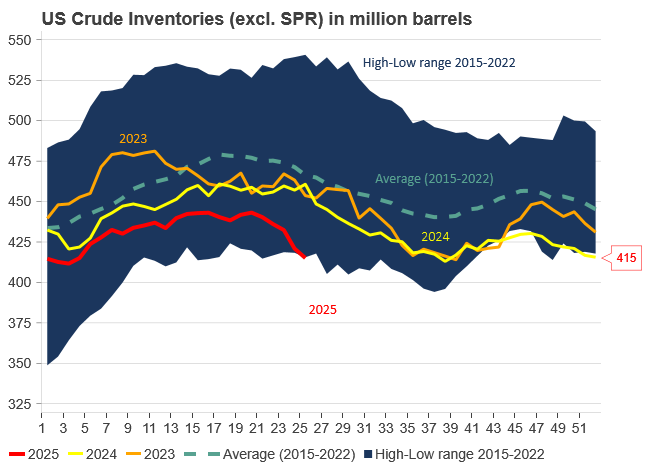

Commercial crude inventories (excl. SPR) fell by 5.8 million barrels, bringing total inventories down to 415.1 million barrels. Now sitting 11% below the five-year seasonal norm and placed in the lowest 2015-2022 range (see picture below).

Product inventories also tightened further last week. Gasoline inventories declined by 2.1 million barrels, with reductions seen in both finished gasoline and blending components. Current gasoline levels are about 3% below the five-year average for this time of year.

Among products, the most notable move came in diesel, where inventories dropped by almost 4.1 million barrels, deepening the deficit to around 20% below seasonal norms – continuing to underscore the persistent supply tightness in diesel markets.

The only area of inventory growth was in propane/propylene, which posted a significant 5.1-million-barrel build and now stands 9% above the five-year average.

Total commercial petroleum inventories (crude plus refined products) declined by 4.2 million barrels on the week, reinforcing the overall tightening of US crude and products.

Analys

Bombs to ”ceasefire” in hours – Brent below $70

A classic case of “buy the rumor, sell the news” played out in oil markets, as Brent crude has dropped sharply – down nearly USD 10 per barrel since yesterday evening – following Iran’s retaliatory strike on a U.S. air base in Qatar. The immediate reaction was: “That was it?” The strike followed a carefully calibrated, non-escalatory playbook, avoiding direct threats to energy infrastructure or disruption of shipping through the Strait of Hormuz – thus calming worst-case fears.

After Monday morning’s sharp spike to USD 81.4 per barrel, triggered by the U.S. bombing of Iranian nuclear facilities, oil prices drifted sideways in anticipation of a potential Iranian response. That response came with advance warning and caused limited physical damage. Early this morning, both the U.S. President and Iranian state media announced a ceasefire, effectively placing a lid on the immediate conflict risk – at least for now.

As a result, Brent crude has now fallen by a total of USD 12 from Monday’s peak, currently trading around USD 69 per barrel.

Looking beyond geopolitics, the market will now shift its focus to the upcoming OPEC+ meeting in early July. Saudi Arabia’s decision to increase output earlier this year – despite falling prices – has drawn renewed attention considering recent developments. Some suggest this was a response to U.S. pressure to offset potential Iranian supply losses.

However, consensus is that the move was driven more by internal OPEC+ dynamics. After years of curbing production to support prices, Riyadh had grown frustrated with quota-busting by several members (notably Kazakhstan). With Saudi Arabia cutting up to 2 million barrels per day – roughly 2% of global supply – returns were diminishing, and the risk of losing market share was rising. The production increase is widely seen as an effort to reassert leadership and restore discipline within the group.

That said, the FT recently stated that, the Saudis remain wary of past missteps. In 2018, Riyadh ramped up output at Trump’s request ahead of Iran sanctions, only to see prices collapse when the U.S. granted broad waivers – triggering oversupply. Officials have reportedly made it clear they don’t intend to repeat that mistake.

The recent visit by President Trump to Saudi Arabia, which included agreements on AI, defense, and nuclear cooperation, suggests a broader strategic alignment. This has fueled speculation about a quiet “pump-for-politics” deal behind recent production moves.

Looking ahead, oil prices have now retraced the entire rally sparked by the June 13 Israel–Iran escalation. This retreat provides more political and policy space for both the U.S. and Saudi Arabia. Specifically, it makes it easier for Riyadh to scale back its three recent production hikes of 411,000 barrels each, potentially returning to more moderate increases of 137,000 barrels for August and September.

In short: with no major loss of Iranian supply to the market, OPEC+ – led by Saudi Arabia – no longer needs to compensate for a disruption that hasn’t materialized, especially not to please the U.S. at the cost of its own market strategy. As the Saudis themselves have signaled, they are unlikely to repeat previous mistakes.

Conclusion: With Brent now in the high USD 60s, buying oil looks fundamentally justified. The geopolitical premium has deflated, but tensions between Israel and Iran remain unresolved – and the risk of missteps and renewed escalation still lingers. In fact, even this morning, reports have emerged of renewed missile fire despite the declared “truce.” The path forward may be calmer – but it is far from stable.

Analys

A muted price reaction. Market looks relaxed, but it is still on edge waiting for what Iran will do

Brent crossed the 80-line this morning but quickly fell back assigning limited probability for Iran choosing to close the Strait of Hormuz. Brent traded in a range of USD 70.56 – 79.04/b last week as the market fluctuated between ”Iran wants a deal” and ”US is about to attack Iran”. At the end of the week though, Donald Trump managed to convince markets (and probably also Iran) that he would make a decision within two weeks. I.e. no imminent attack. Previously when when he has talked about ”making a decision within two weeks” he has often ended up doing nothing in the end. The oil market relaxed as a result and the week ended at USD 77.01/b which is just USD 6/b above the year to date average of USD 71/b.

Brent jumped to USD 81.4/b this morning, the highest since mid-January, but then quickly fell back to a current price of USD 78.2/b which is only up 1.5% versus the close on Friday. As such the market is pricing a fairly low probability that Iran will actually close the Strait of Hormuz. Probably because it will hurt Iranian oil exports as well as the global oil market.

It was however all smoke and mirrors. Deception. The US attacked Iran on Saturday. The attack involved 125 warplanes, submarines and surface warships and 14 bunker buster bombs were dropped on Iranian nuclear sites including Fordow, Natanz and Isfahan. In response the Iranian Parliament voted in support of closing the Strait of Hormuz where some 17 mb of crude and products is transported to the global market every day plus significant volumes of LNG. This is however merely an advise to the Supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and the Supreme National Security Council which sits with the final and actual decision.

No supply of oil is lost yet. It is about the risk of Iran closing the Strait of Hormuz or not. So far not a single drop of oil supply has been lost to the global market. The price at the moment is all about the assessed risk of loss of supply. Will Iran choose to choke of the Strait of Hormuz or not? That is the big question. It would be painful for US consumers, for Donald Trump’s voter base, for the global economy but also for Iran and its population which relies on oil exports and income from selling oil out of that Strait as well. As such it is not a no-brainer choice for Iran to close the Strait for oil exports. And looking at the il price this morning it is clear that the oil market doesn’t assign a very high probability of it happening. It is however probably well within the capability of Iran to close the Strait off with rockets, mines, air-drones and possibly sea-drones. Just look at how Ukraine has been able to control and damage the Russian Black Sea fleet.

What to do about the highly enriched uranium which has gone missing? While the US and Israel can celebrate their destruction of Iranian nuclear facilities they are also scratching their heads over what to do with the lost Iranian nuclear material. Iran had 408 kg of highly enriched uranium (IAEA). Almost weapons grade. Enough for some 10 nuclear warheads. It seems to have been transported out of Fordow before the attack this weekend.

The market is still on edge. USD 80-something/b seems sensible while we wait. The oil market reaction to this weekend’s events is very muted so far. The market is still on edge awaiting what Iran will do. Because Iran will do something. But what and when? An oil price of 80-something seems like a sensible level until something do happen.

-

Nyheter4 veckor sedan

Nyheter4 veckor sedanUppgången i oljepriset planade ut under helgen

-

Nyheter3 veckor sedan

Nyheter3 veckor sedanMahvie Minerals växlar spår – satsar fullt ut på guld

-

Nyheter4 veckor sedan

Nyheter4 veckor sedanLåga elpriser i sommar – men mellersta Sverige får en ökning

-

Nyheter2 veckor sedan

Nyheter2 veckor sedanOljan, guldet och marknadens oroande tystnad

-

Analys4 veckor sedan

Analys4 veckor sedanVery relaxed at USD 75/b. Risk barometer will likely fluctuate to higher levels with Brent into the 80ies or higher coming 2-3 weeks

-

Nyheter2 veckor sedan

Nyheter2 veckor sedanJonas Lindvall är tillbaka med ett nytt oljebolag, Perthro, som ska börsnoteras

-

Analys3 veckor sedan

Analys3 veckor sedanA muted price reaction. Market looks relaxed, but it is still on edge waiting for what Iran will do

-

Nyheter2 veckor sedan

Nyheter2 veckor sedanDomstolen ger klartecken till Lappland Guldprospektering